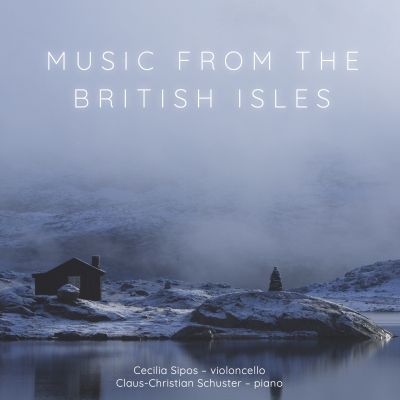

Music from the British Isles

Cecilia Sipos – Violoncello

Claus-Christian Schuster – Klavier

Rebecca Clarke: Epilogue · May Mukle: The light Wind & Hamadryad · Ralph Vaughan Williams: Six Studies in English Folk-Song · Margot Wright: Three Northumbrian Folk Songs · Imogen Holst: “The Fall of the Leaf” for Solo Violoncello · Imogen Holst: Two Scottish Airs · Howard Ferguson: Five Irish Folk-Tunes · Rebecca Clarke: I'll bid my heart be still

© 2025 · iTunes · Spotify · Preis: € 20,– Die CD ist erhältlich auf Bestellung oder auf Amazon

Eine Hommage an die britische Cellistin May Mukle (1880–1963)

Unsere Spurensuche entlang der Lebenswege jener außergewöhnlichen Frauen, die sich über die gesellschaftlichen Vorurteile hinwegsetzten und als Violoncellistinnen erfolgreich waren, führte uns zu der britischen Cellistin May Mukle – auch die „weibliche Casals“ genannt. Nicht nur ihre internationale Karriere als Solistin und Kammermusikerin war bemerkenswert, sondern auch ihre unermüdliche Arbeit für die Anerkennung und Etablierung der britischen Musikerinnen und Komponistinnen des 20. Jahrhunderts. Dank ihr wurde das Cellorepertoire mit einigen ihr persönlich gewidmeten Kompositionen bereichert. Ralph Vaughan Williams, Rebecca Clarke und Imogen Holst sind dabei unsere Kronzeugen in einem sehr selten gespielten Programm des österreichischen Konzertlebens.

Mit dieser Aufnahme wollen wir May Mukle einen Denkmal setzen!

Aufnahme: 25.–28. 5. 2024

Brahms Museum, Mürzzuschlag

Tonmeister, Aufnahmeleiter: Jens Jamin

In 1904, the Munich publishing house Georg Müller printed a collection of essays entitled ‘Das Land ohne Musik. Englische Gesellschaftsprobleme’ (The Land Without Music: English Social Problems) by the then 31-year-old Oscar A. H. Schmitz. Ten years later, at the beginning of the First World War, the fourth edition of the immensely successful book, now, perfectly in line with the ever NEEDS A HYPHEN growing chauvinism of the day, “cleansed” of “unnecessary” foreign words, was already in print, from which the following passage is still frequently quoted today:

‘I have long sought to identify the deficiency that is so palpable behind so many English virtues and has such a paralysing effect. I have asked myself what this people lacks: kindness, humanity, piety, humour, artistic sensibility? No, all these qualities are present in England, some even more visibly than in our country. And finally I found something that distinguishes the English from all other civilised peoples to an astonishing degree, a deficiency that everyone admits – so it is not really a discovery – but whose significance has probably not yet been emphasised: THE ENGLISH ARE THE ONLY CIVILISED PEOPLE WITHOUT A MUSIC OF THEIR OWN (except for popular tunes). This does not merely mean that they have less refined ears, but that their whole life is poorer. To have music in you, even if only a little, means being able to lose yourself, to endure dissonance, even to linger in it, because it can be resolved into harmony. Music gives wings and makes everything wonderful seem comprehensible.’

Now, nothing would be easier than to call the young author a deluded fool who has been led astray by rampant chauvinism. But ever since the Berlin publishing house Aufbau-Verlag published a three-volume edition of Oscar Schmitz's diaries in 2006/07, meticulously edited by Wolfgang Martynkewicz, we know that this would be a hasty and superficial judgement. In fact, Oscar Schmitz could be seen as a highly characteristic figure amongst his generation, with all its surprising creative variety. After all, in addition to Max Reger, Arnold Schönberg and Maurice Ravel, it included – as if to show how wrong Schmitz was – a remarkable number of very different and original composers, amongst whom we could mention Frank Bridge and Gustav Holst, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Roger Quilter, John Ireland and Joseph Holbrooke, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and William Havergal Brian, to name at random but a few of the many dozens, who testify impressively to the incredible variety and richness of British music in this period.

From 1897 onwards, Schmitz belonged to the circle around the original and recondite poet Stefan George (1868-1933), from whom he soon turned away, even becoming an acute mocker of this group, which gradually was becoming a kind of “secret church”. (For the musical world the main importance of Stefan George lies in the fact that he inspired Schoenberg’s Opus 15, which remains a landmark in the history of music.) Hedwig Schmitz, Oscar's younger sister, became the wife of Austrian painter Alfred Kubin (1877-1959) in the same year the fateful book was published, and Oscar Schmitz later undertook extensive travels with his brother-in-law, the records of which show him again as a very sensitive and intelligent observer. As half-baked and problematic as many of Oscar Schmitz's thoughts and conclusions may be, it is not difficult to find the real reason for the astonishing longevity with which the ominous title of his book has lodged itself in the minds of many music lovers around the world. For it cannot be seriously disputed that during the very years in which the overwhelming majority of the compositions that dominate the programmes of the world's concert halls and opera houses today were written – that is, very roughly speaking, between the middle of the 18th and the end of the 19thcenturies – it is very difficult to discern an authentic compositional voice from the British Isles. Isolated figures such as John Field, who was born in Dublin and died in Moscow (and who, in spite of the decade spent in his youth in London as a student of Muzio Clementi, occupies a clearly detached position), or William Sterndale Bennett, who was fascinated by the genius of Mendelssohn and had his ideal home in Germany, but died in Saint John's Wood in 1875, or the child prodigy Samuel Wesley, who in London at times was dubbed “the English Mozart”, but found hardly any echo outside England except for his hymns, do little to change this overall picture.

Between the death of Henry Purcell (1695) and the first appearance of the triad that heralded the revival of English music from around 1880 (Hubert Parry, *1848 – Charles Stanford, *1852 – Edward Elgar, *1857), the British Isles contributed virtually nothing to the treasure trove of ‘immortal’ music.

This seems all the more astonishing, given that London, particularly during this period, became one of the world's leading music centres, thanks in large part to numerous ‘foreigners’ such as Georg Friedrich Händel, Johann Christian Bach and Muzio Clementi. Its importance was confirmed by musical highlights such as Joseph Haydn's two stays in London, but also by a flourishing music publishing industry with international appeal. Haydn's and Beethoven's relationships with British publishers and organisations are symptomatic of this development. London was also to become influential and decisive for the development of professional concert life as we know it today: it is no coincidence that the rebirth of English music was preceded by the organisational achievements of ‘music managers’ such as John Ella, who founded the ‘Musical Union’ in 1845.

The striking lack of original contributions, against the previous history of centuries of exceptional originality and striking individuality, as manifested in the works of John Dunstable, John Taverner, Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, John Dowland and, just before the unpredictable “gap”, Henry Purcell, is surprising and perplexing.

To counterbalance this strange phenomenon we can clearly see that nowhere else in the world has folk music been accorded such sustained and widespread interest already during its primary heyday, i. e. way before its revival towards the end of the 19th century, as in the British Isles. The traditional description of this cultural field – England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales – clearly reveals a distinct Celtic element, and it is precisely this Celtic element that is the focus of the present recording. Maybe it is exactly this Celtic element flavour, which establishes an ideal link to an immemorial, pre-Roman layer of Europe’s cultural history, which is responsible for the fascination that has been accorded to the folk music of the British Isles.

(The passionate search for an individual national identity also led James Macpherson to produce those virtuoso forgeries which, under the fantasy name ‘Ossian’, were a source of fascination throughout Europe for decades, and to which even Franz Schubert (like almost all his contemporaries) willingly succumbed.)

While the far less original examples of “national melodies”, which – thanks to the insatiable activity of Scottish publishers – became the basis for almost countless folk song arrangements by Haydn, Beethoven, Koželuh and others at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, have remained fairly present in concert practice to this day, it took quite a while for more authentic and original material to arouse the interest of composers. Some of the most successful fruits of this subsequent engagement, which was particularly intense in the first half of the 20th century, are now brought together here – without, of course, any claim to completeness.

Our journey begins – with deliberate irony – with Rebecca Clarke's ‘Epilogue’, dedicated to the Portuguese student and partner of Pablo Casals, Guilhermina Suggia (1885-1950), a work of particular intensity and originality: exactly when it was written (in any case between 1921 and 1931) remains unclear. The first confirmed performance probably took place in January 1932: May Mukle (1880-1963), the “heroine”of our anthology, and her older sister Anne (1864-1941) were the performers of this moving and deeply personal composition.

Our heroine May Mukle then takes to the podium herself as a creative author: her two ‘Fancies’, probably written around 1917/18, bear witness to a talent that went far beyond the everyday; but our research into other compositions by her has so far been unsuccessful. Even her origins in a German-British marriage (her father, a pianist, organist and instrument maker, apparently came from Furtwangen in the Black Forest) have not been completely clarified. There is no doubt, however, that she was one of the most vital and convincing representatives in her field and who remained internationally active and successful even in her old age.

It is no wonder that a composer of the calibre of Ralph Vaughan Williams, who was the most ardent and creative follower of the folksong movement initiated by Lucy Broadwood and Cecil Sharp, took notice of her and dedicated the simple yet touching cycle Six Studies in English Folk Song to her in 1926. The sisters May and Anne premiered it on 4 June 1926 at the legendary Scala Theatre in London as part of a festival organized by the Folk Song Society, founded in 1898.

(This folklore association merged in 1932 with the English Folk Dance Society, founded by Cecil Sharp in 1911, to form the EFDSS, which is still active today. The Scala Theatre on Charlotte Street/Tottenham Court Road, which had existed since 1772 and was demolished only in 1969 after a devastating fire, was to make its last appearance just before its tragic end as the setting for the Beatles film ’A Hard Day's Night’ (1964)).

In contrast to Ralph Vaughan Williams, the younger pianist Margot Wright (married name Pacey) remained relatively unknown as a composer. She owes her posthumous fame mainly to her brief stint as accompanist to her dear friend Kathleen Ferrier, who was a year younger than her and became the godmother of her daughter Prunella in 1949. Towards the end of her long life, which she spent mostly in Sheffield, and a full 40 years after Kathleen Ferrier's death, Wright created a simple memorial to her friend with the Three Northumbrian Folk Songs, in which she wistfully evoked the vocal artistry of this unforgettable legend.

The two following works are also remarkable testimonies of a selfless and unpretentious devotion to a pre-existing treasure. They were written by Imogen Holst, who grappled with the doubly difficult fate of being the daughter of a famous father and the secretary of an idolised genius, with great dignity. The daughter of Gustav Holst acted from 1952 onwards as amanuensis of her idol Benjamin Britten in Aldeburgh. It is probably the noble modesty and reserve of this highly talented musician, that deprived us of a far more extensive oeuvre. But the two compositions brought together here bear eloquent testimony to a distinctive and thoroughly independent creative talent: the solo work The Fall of the Leaf is based on a melody from the late 16th or early 17th century, which frames three variations. The work was premiered on 4 February 1963 at London's Wigmore Hall by its dedicatee, the cellist, pianist and composer Pamela Hind O'Malley (1923-2006), who had been Imogen's colleague as teacher at Dartington Hall School (near Totnes, Devon) for several years.

The premiere of the Two Scottish Airs, written 30 years earlier in Imogen's youth, probably took place on 19 April 1933 as part of a broadcast from the Edinburgh BBC studios on Queen Street. Imogen Holt remained true to her love of authentic folk music, which she had professed from the very beginning, throughout her entire life.

Howard Ferguson was only 19 years old when, in the final year of his composition studies at the Royal College of Music, he transferred from the class of R. O. Morris to that of Ralph Vaughan Williams. In the same year, he completed his first ambitious work, the Five Irish Folk Tunes, which was immediately accepted for publication by Oxford University Press. The starting point for this original suite are melodies from the vast collection of folk songs compiled by the Dublin-based historian, archaeologist, painter and musician George Petrie (1790-1866). Despite the encouraging success of this first composition, Ferguson soon came to the conclusion that he would not be sufficiently productive as a composer; he subsequently concentrated more on his role as pianist with the Ensemble Players, which he had founded, and for whom in 1933 he was to write his best-known work, an octet for clarinet, horn, bassoon and string quintet. In the last 40 years of his life, sadly, he stopped composing altogether.

To conclude our exploration of the Celtic roots of 20th-century British music, we return to the composer whose music opened this tour. Rebecca Clarke originally intended this touching meditation on the Scottish folk song ‘I'll bid my heart be still’, for viola, the composer’s own instrument; the cello verS!ion presented here is an alternative sanctioned by Clarke. It was composed in March 1944 as a wedding gift on the occasion of her late marriage (New York, September 23rd, 1944) to the Scottish composer, pianist and Bach specialist James Friskin (1886-1967).

This final point of our journey provides a welcome opportunity to mention briefly the complexity of the relationship between the texts and melodies of the folk songs that were later arranged. The ‘Old Scottish Border Melody’, so poignantly and profoundly arranged by Rebecca Clarke, apparently dates back to the 16th century and supposedly was supposedly accompanied by the following text:

O once my thyme was young,

It flourished night and day;

But by there cam‘ a false young man,

And he stole my thyme away.

Within my garden gay

The rose and lily grew;

But the pride o’ my garden is withered away,

And it's a‘ grown o'er wi’ rue.

Farewell, ye fading flowers,

And farewell, bonnie Jean;

But the flower that is now trodden under foot

In time it may bloom again.

In the first volume of ‘Albyn's Anthology’ published in 1816 by Alexander Campbell (1764-1824), we encounter the song with new lyrics by Thomas Pringle (1789-1834), a Scottish poet and friend of Walter Scott; it is to these that the composer apparently refers in her arrangement:

I'll bid my heart be still,

And check each struggling sigh!

And there's none e'er shall know

My soul's cherished woe,

When the first tears of sorrow are dry.

They bid me cease to weep,

For glory gilds his name;

Ah! ‘tis therefore I mourn --

He ne'er can return

To enjoy the bright noon of his fame.

While minstrels wake the lay

For peace and freedom won,

Like my lost lover's knell

The tones seem to swell,

And I hear but his death-dirge alone.

My cheek has lost its hue,

My eye grows faint and dim,

But ‘tis sweeter to fade

In grief's gloomy shade,

Than to bloom for another than him.

The poet, who lived in South Africa for several years from 1820 (and is therefore considered the ‘father of South African literature’), rendered great services in the fight against the slave trade – and, a few months before his death in 1834, had the satisfaction of the official ban on this barbaric practice, which, sad to say, almost 200 years later, has still not been completely eradicated. Yet this very fact reminds us once more of the immortal truth, that – as Dryden and Purcell stated in 1692 – “music for a while shall all your cares beguile”.

© Claus-Christian Schuster, 2025